We often feel more connected to something we have built ourselves, even if it is as simple as a bookshelf from IKEA. The IKEA Effect is a cognitive bias where we overvalue products or items we have helped to create or assemble, regardless of their actual quality or worth. This effect helps explain why building or customising something ourselves can make it seem more special or important.

This bias is not just about furniture—it can affect how we view everything from crafts to business projects. By understanding the IKEA Effect, we can become more aware of how our effort shapes how we value the things around us.

Key Takeaways

- The IKEA Effect makes us value self-created items more highly.

- Our feelings of ownership and effort play a key role in this bias.

- Knowing about this bias helps us understand our choices as consumers.

Understanding the IKEA Effect Cognitive Bias

The IKEA Effect shows us that personal effort often changes how much we value what we own. When we build or create something ourselves, we tend to see it as more valuable—sometimes even more than items made by experts.

Definition of the IKEA Effect

The IKEA Effect is a cognitive bias that leads people to place a higher value on objects they help assemble or create. This term comes from the Swedish furniture retailer IKEA, known for selling products that require home assembly.

This bias means we might think a bookshelf we built ourselves is worth more than a ready-made one, even if the quality is the same.

Companies use this effect by letting customers take part in building or customising products. For example, “Build-A-Bear” or some restaurants let us choose ingredients or assemble our own items, encouraging a sense of ownership and pride.

Origins and Key Researchers

The IKEA Effect was first described by researchers Michael I. Norton, Daniel Mochon, and Dan Ariely. Their 2011 study found that people were willing to pay much more for furniture they assembled than for equivalent items they did not build.

Their experiments included boxes, LEGO sets, and furniture, showing that people value their self-made items more highly. Even when the finished products were not perfect, the sense of accomplishment and effort increased their perceived worth.

The research demonstrated that the IKEA Effect is not limited to furniture. It appears in different tasks and products, as long as we are involved in the creation process.

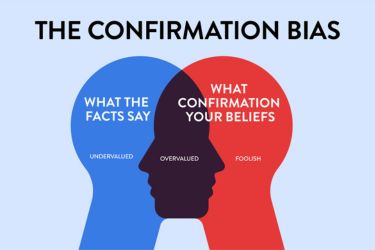

Relation to Cognitive Biases

The IKEA Effect is one of many cognitive biases that shape our decisions. Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts that influence how we think, feel, and act in daily life.

Specifically, the IKEA Effect is related to ownership bias, where people value things more simply because they own them. It also connects to the effort justification bias, which means we rate results more highly if we worked hard to achieve them.

Understanding these connections helps us see why the IKEA Effect is strong and why it affects choices beyond assembling furniture. Recognising these biases can help us make more objective decisions about the things we create or buy.

Psychological Mechanisms Behind the IKEA Effect

The IKEA Effect is shaped by how our minds process effort, reward, and ownership. Several key psychological mechanisms influence why we value what we help to create.

Effort Justification and Cognitive Dissonance

When we invest time and effort into building something, we are more likely to value it. This is known as effort justification. We want our energy to feel meaningful and not wasted. Because of this, we convince ourselves that the finished product is worth more because we worked for it.

Cognitive dissonance plays a part as well. If the outcome does not match the effort we put in, we feel uncomfortable. To resolve this feeling, we tend to see our creations in a more positive light. We reassure ourselves that all the hard work was worthwhile.

This process is seen in many situations, from assembling flat-pack furniture to creating a personal project. Effort transforms an ordinary object into something special simply because it required our labour.

Key Points

- People value self-made products higher.

- Effort leads to increased attachment.

- Justifying effort helps relieve uncomfortable feelings.

Emotional Rewards and Sense of Accomplishment

Taking part in making something gives us emotional satisfaction. The emotional reward stems from turning our efforts into a physical result we can see and use. This sense of accomplishment can make the finished product feel unique and more meaningful to us.

We get a boost in confidence when we finish a task ourselves. This is especially true if the task is challenging. The small successes we experience along the way build up this sense of accomplishment, pushing us to value the outcome even more.

Our feelings of pride and satisfaction become tied to the object itself. Because we played a direct role in its creation, it becomes a reminder of our skills and effort.

Emotional Benefits:

- Increased self-esteem

- Lasting pride in completed work

- Personal connection to the end result

The Endowment Effect and Ownership

The endowment effect describes how we value things we own more than those we do not. By assembling or creating a product ourselves, we develop a stronger sense of ownership over it. This ownership increases the object’s perceived value.

When we take part in the creation process, our involvement changes how we relate to the final product. We no longer see it as just another item. It becomes our item, with a special status.

This psychological phenomenon is powerful in consumer behaviour. The act of assembling something ourselves not only makes it ours but makes us believe it is worth more than the same item made by someone else.

Ownership Effects:

- Stronger personal attachment

- Higher willingness to keep the item

- Increased perceived value due to ownership

Real-World Manifestations and Examples

We encounter the IKEA Effect in different areas of our lives, especially when we take part in building, crafting, or customising things. Our effort often leads us to value what we have made more highly and grow more attached to these creations.

Assembling Furniture and Customer Assembly

When we assemble flat-pack furniture from brands like IKEA, we do more than follow instructions. Our hands-on effort makes us feel as though we had a role in the product’s creation. Research shows that customers rate these self-assembled items as more valuable compared to furniture that comes pre-assembled.

This effect is not limited to IKEA. Companies like LEGO and Build-A-Bear attract customers by letting them build or customise their own products. DIY experience kits and meal kits use the same principle—our input increases our satisfaction and sometimes even our loyalty. Businesses use this bias to encourage us to buy, recommending products or services we can make “our own”.

| Brand | Type of Assembly | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| IKEA | Furniture building | BILLY Bookcase |

| LEGO | Creative assembly | LEGO City Fire Station Set |

| Build-A-Bear | Custom assembly | Create-your-own bear |

Impact on Hobbies and Creativity

Hobbies that require building or crafting—such as model building, knitting, or painting—also reveal the IKEA Effect. We tend to appreciate our handmade items or artworks more than ready-made ones. The sense of achievement comes from both the process and the finished product.

This attachment can lead to collections we proudly display or gifts we cherish when they are handmade. Creativity increases our appreciation, making what we produce feel special and significant. Even if the final result is imperfect, our investment of time and effort makes it more valuable in our eyes.

List of common hobbies influenced by the IKEA Effect:

- Gardening (growing our own plants)

- Cooking or baking from scratch

- Making jewellery

- DIY home décor projects

The Role of Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem

Our confidence in our ability to complete tasks—called self-efficacy—plays a big role in the IKEA Effect. Building or finishing something ourselves boosts our belief in our skills. This, in turn, strengthens our self-esteem because we see what we are capable of creating.

When we assemble furniture or take part in creative hobbies, we test our abilities and often surprise ourselves with what we can do. Successfully completing the task, even if it is challenging, can leave us feeling more competent and proud.

Self-efficacy and self-esteem often feed off each other, making us more willing to try new projects. As we become more confident, the satisfaction we get from hands-on tasks often grows even stronger.

Business and Consumer Implications

Understanding the IKEA Effect helps us see why customers value self-assembled or customised products. Firms use this bias to boost customer engagement, satisfaction, and even profitability.

Influence on Value Perception

When we put effort into building or customising something—like assembling flat-pack furniture for our home—we often value it more than pre-made items. This cognitive bias, sometimes called "labour leads to love," means our hard work increases our emotional bond to the end product.

This phenomenon isn't limited to furniture. For example, with Build-A-Bear, customers assemble their own stuffed animals, resulting in stronger attachment and a willingness to pay more. Even simple interaction, such as choosing kitchen ingredients or customising decor, triggers the effect.

Firms leverage the IKEA Effect to justify price premiums and encourage repeat business. Our sense of ownership and pride in completing a task often outweighs the minor inconveniences of assembling or customising. Research finds that, in many cases, we are willing to pay significantly more for products we help create.

Applications in Product Design and Marketing

Businesses integrate the IKEA Effect by designing products that require some customer involvement. Companies like IKEA purposefully package furniture for self-assembly, which reduces costs and increases perceived value for customers.

In product design, offering choices for personalisation—be it colour, style, or features—reinforces our connection to the item. This turns a mass-produced object into something that feels unique and "about" us. We see this in custom trainers, meal kits, and even tech gadgets.

Marketing strategies also highlight involvement. Brands use messaging like "Make it your own" or "Designed by you" to tap into the IKEA Effect. This approach engages us as co-creators, not just buyers, making products for our home feel more personal and meaningful. As a result, customer satisfaction and brand loyalty both rise.

Limitations, Criticisms, and Broader Impact

The IKEA Effect shows how our effort can inflate the value we assign to things we've made or assembled. Despite its prevalence, several factors limit its reach and change its impact based on context, culture, and long-term outcomes.

When the IKEA Effect May Not Apply

The IKEA Effect does not always appear in every situation. If a task is too difficult or the finished product looks poor, we may not value the result more, even if we invested effort.

For example, frustration or failure during assembly can weaken or cancel out the effect. In group projects, the sense of personal ownership is diluted, reducing the bias.

We must keep in mind that cognitive biases often interact. Opinions from others, teamwork, and personal interest can limit how much extra value we assign based on our own effort.

Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Value

Different cultures may not value personal effort in the same way. In some places, community or family achievements matter more than individual creation. This can reduce the IKEA Effect when people work together or share responsibilities.

Research suggests cultures that focus on self-reliance and independence might show a stronger bias, while others that prioritise cooperation may not. The way value is assigned to self-made work can vary with local norms and beliefs.

It's important for companies and designers to consider these cultural differences when using co-creation or self-assembly strategies. One approach rarely fits all.

Long-Term Effects on Decision-Making

The IKEA Effect can lead us to make decisions that overvalue effort over actual quality or function. Over time, this bias may cause us to stick with products or ideas we worked hard on, even when better options are available.

In workplaces, this can mean holding on to outdated or inefficient solutions simply because we helped create them. Businesses might risk ignoring valuable feedback if individuals are too attached to their own creations.

To manage these risks, it helps to seek outside opinions and regular evaluation. Staying aware of related cognitive biases can guide better, more objective decision-making.

Frequently Asked Questions

The IKEA effect shapes how we value products we help create or assemble. It can change how we act as consumers, affect how we connect with others, and even influence the way businesses operate.

What are common examples of the IKEA effect in consumer behaviour?

We often pay more attention to items we've put together ourselves, like IKEA furniture or customisable trainers.

Some people keep handmade gifts or DIY projects for longer because they feel attached to their own effort. Parents might also save their children's school projects for the same reason.

How does the IKEA effect influence the value perception of self-assembled products?

When we assemble something, we tend to believe it is worth more than an identical ready-made item. Our effort and time make us see our finished work as higher in value and importance.

Studies show that people are even willing to spend extra money on things they've assembled themselves.

In what ways can the IKEA effect impact personal relationships?

We sometimes value relationships or friendships more when we've worked hard to build or maintain them. Solving problems together or investing time in each other can create stronger bonds.

This effect can also lead people to overlook flaws because they remember the effort put into the relationship.

How is the IKEA effect utilised in marketing strategies?

Many companies encourage customers to personalise or build part of a product. For example, brands may offer customisable trainers or allow users to design their own products online.

Businesses use this approach to make customers feel connected to the product, which can increase satisfaction and loyalty.

What implications does the IKEA effect have for business and management?

Managers may get their teams to contribute ideas or help with projects so employees feel a sense of ownership. This can raise motivation and engagement at work.

However, leaders need to be careful, as people may misjudge the value of their own work, which can affect decision-making.

How does the IKEA effect relate to the concept of labour leading to love?

The idea is that when we put effort into something, we grow to like it more. Our work creates a personal link to the outcome, making us feel proud.

This can help explain why we often prefer our own creations and feel satisfied when we have finished a task we worked hard on.