Many of us think we make choices based on logic and facts, but the way information is shown to us can actually change our decisions. Framing bias is when our choices are influenced more by how something is presented than by the actual details. This bias shows up in everything from shopping to voting, even though we might not notice it happening.

We may see the same facts, but if they are worded differently, our reactions and decisions can change. Advertisers, politicians, and the media often use this effect to guide how we think and act, sometimes without us even realising. Understanding framing bias can help us make more balanced and fair decisions.

Key Takeaways

- Framing bias changes how we see and react to information.

- Different types of framing affect our decisions in daily life.

- Learning about framing bias helps us make better, clearer choices.

Understanding the Framing Bias

Framing bias is a form of cognitive bias that shifts our perceptions and decisions based on how information is presented, not just on the facts alone. This bias plays a significant role in how we judge options, risks, and outcomes, even when the underlying information is the same.

Definition and Core Concepts

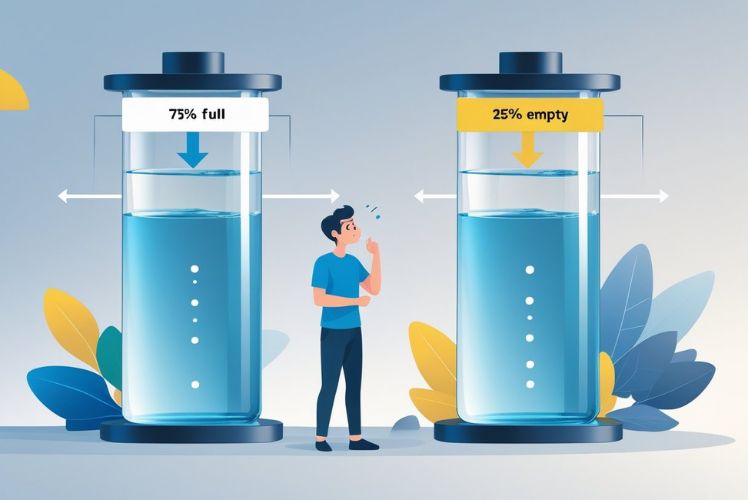

Framing bias refers to the way the wording or context of information affects our decisions. For example, if an option is stated as a gain (“keep £20 out of £50”) versus a loss (“lose £30 out of £50”), we may choose differently, even though both mean the same thing.

This bias is a type of cognitive bias, meaning it is a systematic error in our thinking. It affects everyone, regardless of age or education. Framing can be positive (focused on gains) or negative (focused on losses), and our response can change simply because of this shift in focus.

Key features of framing bias include:

- Focus on presentation, not just facts

- Tendency to react differently to positive or negative wording

- Influence on everyday choices, from health decisions to financial investments

By recognising these patterns, we can become more aware of when framing may be influencing us.

Origins in Cognitive Psychology

Framing bias was first studied in cognitive psychology by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the late 20th century. Their famous "prospect theory" experiments showed how people value potential gains and losses differently depending on how choices are presented.

This work highlighted that our brains are not purely rational when making decisions. Instead, we rely on mental shortcuts, called heuristics, which save time but can lead to consistent errors like framing bias.

Framing connects closely with our emotional responses. If something is presented in a threatening way, we may react with caution; if it sounds like an opportunity, we might take more risks. Framing bias helps explain why we often make choices that seem irrational in hindsight.

Distinction from Other Cognitive Biases

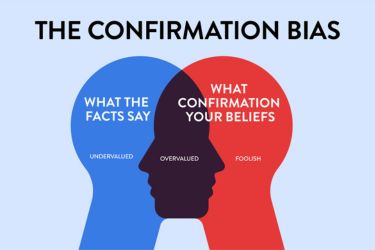

Framing bias is different from other cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias or anchoring bias. While confirmation bias involves searching for evidence that supports our beliefs, framing bias is about how the same information, presented differently, changes our choice.

Anchoring bias is another related concept, which happens when we rely too heavily on the first piece of information we receive. In contrast, framing bias is driven by the overall way information is packaged or "framed", not just the starting point.

To summarise the differences:

| Bias Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Framing Bias | Choice changes based on positive or negative presentation |

| Confirmation Bias | Seeking information that supports our existing views |

| Anchoring Bias | Relying too much on initial information |

Understanding these differences helps us see what makes the framing bias unique in shaping our everyday thinking.

How the Framing Effect Influences Decision-Making

The framing effect shapes the way we interpret choices by changing how information is presented. Our decisions are often swayed not only by facts, but by the context and wording surrounding those facts.

Role in Everyday Decisions

The framing effect is present in many daily situations. For example, when we see products advertised as “95% fat-free” instead of “5% fat”, we are more likely to view them positively. The positive wording makes the product seem healthier, even though the actual information is the same.

When reading news or hearing advice, the way information is framed can shift our opinions. A report about “success rates” sounds more encouraging than one about “failure rates”, even if they come from the same statistics.

This bias also appears when we make financial decisions. We might prefer an investment described as having a “chance to gain” rather than one described in terms of what might be lost, even if the underlying risk is identical.

Impact on Risk Perception

Framing strongly affects our feelings about risks and benefits. How a choice is framed can either make us more likely to take a risk or more cautious. For instance, when options are presented as avoiding a loss, we often act more conservatively than when the same options are shown as a chance to gain something.

In healthcare, patients react differently when procedures are explained with “survival rates” as opposed to “mortality rates”. Even when the numbers match, a positive frame can lead people to agree to more treatments or make different health decisions.

Key Examples:

- Gains vs Losses: “You have a 90% chance of surviving” versus “You have a 10% chance of dying”

- Safety messaging: “Save 100 out of 600 people” instead of “400 people will die”

Mechanisms Behind the Bias

The framing effect relies on cognitive shortcuts, or heuristics, that our brains use to make decisions quickly. We rely on the surface of the information, like wording and emphasis, because it saves mental effort. This can lead us to overlook important facts beneath the surface.

Emotional reactions also play a role. A positive frame sparks hope, while a negative frame brings caution or fear. Because of this, we might not evaluate all details logically.

Bias from framing is stronger when we are tired, distracted, or have limited information. The effect is widespread, making it important for us to notice how options are presented and to question our first impressions.

Types of Framing Bias

Framing bias appears in different ways depending on how information is presented. We can see unique effects in choices involving risk, descriptions of product or option attributes, and how positive or negative outcomes are highlighted.

Risky Choice Framing

Risky choice framing happens when our decisions about risk change depending on how the options are worded. For example, when given a health scenario, stating “90 out of 100 people survive this surgery” leads to more people choosing surgery than “10 out of 100 people die from this surgery”.

We tend to select risky choices if potential losses are made clear, but are more cautious when potential gains are stressed. This bias is common in areas like health, insurance, and finance. Marketers and policymakers often use different frames to influence risk-taking behaviours. Understanding risky choice framing helps us question whether our decisions are based on facts or just the way options are shown.

Attribute Framing

Attribute framing refers to how we evaluate a product, person, or experience based on whether its features are presented as positive or negative. For instance, ground beef described as “80% lean” is often preferred over “20% fat”, even though both mean the same thing.

Small changes in language lead us to focus on certain qualities over others. This can sway our opinions and purchasing choices. Attribute framing is widely used in advertising and political messaging. By recognising it, we can better spot when our views are shaped by framing rather than actual content.

Gain Frame Versus Loss Frame

A gain frame highlights the positive outcomes of a choice, while a loss frame stresses possible negative results. For example, a sign that says “Save £50 if you pay early” (gain frame) will feel different from one that says “Lose £50 if you pay late” (loss frame).

Research shows we tend to avoid risks when information is framed as gains, but take more risks when it is framed as losses. This effect is linked to loss aversion: people dislike losing something more than they enjoy gaining the same thing. Such framing is powerful in public health campaigns, financial advice, and negotiations. Spotting the type of frame used can help us make more balanced decisions.

Theoretical Foundations and Influential Research

When exploring framing bias, it is useful for us to examine the psychological theories and experimental research that shaped our understanding. Key studies and theory developments help us see how framing affects our decision-making.

Prospect Theory and Loss Aversion

Prospect theory, developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, is a core idea behind framing bias. This theory explains how we assess losses and gains differently when making decisions under risk. We tend to be more sensitive to potential losses than to equivalent gains, a concept called loss aversion.

When information is framed to highlight losses rather than gains, our choices often shift. For example, the same outcome may seem more alarming if described in terms of lives lost instead of lives saved. This effect appears in everything from economic decisions to health advice, showing how frames change our perception of value and risk.

Kahneman and Tversky’s work challenged the idea that people always act rationally. Instead, their findings show that how options are presented—using loss frames or gain frames—can strongly influence our judgements.

Notable Experiments and Case Studies

One classic experiment by Tversky and Kahneman, known as the Asian Disease Problem, tested how different ways of describing a health crisis shaped decisions. Participants reacted differently to solutions that were framed positively (lives saved) versus negatively (lives lost), even though the facts were the same.

Other research extends these results across various fields, including finance and media. For example, news stories that frame events in terms of threats or dangers can influence public concern and opinion. In marketing, describing a product’s benefits instead of its drawbacks can sway our choices.

Multiple studies confirm that framing effects are not limited by culture or context. They show up wherever people must make judgements and decisions with imperfect information, underlining the broad relevance of this bias in real-world settings.

Applications and Real-World Implications

The framing effect shapes our decisions in powerful ways. How information is presented can nudge us to react differently, even when the facts remain unchanged.

Marketing and Advertising Strategies

Marketers use the framing bias to guide our buying choices. Presenting a discounted price as “Save £50” instead of “Pay £450” makes the offer feel more attractive, despite the actual cost being the same. This positive framing focuses our attention on gains, which increases our likelihood of purchasing.

Subscription models also use strategic framing. Saying a service costs “just £10 per month” feels more manageable than describing it as “£120 per year”, even though the total is identical. Limited-time offers and exclusive deals use loss frames to create a sense of urgency or fear of missing out.

Marketers rely on these tactics because the framing effect reliably alters consumer decision making. Understanding the methods used can help us make more deliberate purchasing decisions.

Political and Media Influence

Politicians and news outlets often frame issues in ways that shape how we interpret events. For example, one channel might describe a budget cut as “streamlining government waste”, while another labels it “slashing vital services”. Both are talking about the same policy, but the frame alters public reaction.

In elections, campaign messages frequently use gain or loss frames. Highlighting potential benefits (“improving schools”) encourages support, while loss frames (“risking our children’s future”) can drive fear or opposition. Listeners tend to respond more strongly to losses, making negative framing especially powerful.

Media outlets also select which facts to highlight, shaping which aspects of a story we focus on. This can lead to different opinions and choices, even when audiences review the same information overall.

Health and Medical Decision Scenarios

In the medical field, the framing effect can affect decisions about treatment. Doctors might present the same statistic in two ways: “This procedure has a 90% survival rate” (gain frame) versus “There is a 10% chance of death” (loss frame). Although the numbers are identical, the loss frame often feels riskier, leading patients to refuse treatment.

We also see framing in discussions about disease screening. Saying “200 out of 1,000 patients will be saved” sounds more reassuring than “800 out of 1,000 will die”, despite describing the same risk. This difference impacts patient decision making and consent.

Clear, neutral framing helps patients make choices based on accurate understanding rather than emotional reaction to how information is presented.

Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding the framing bias helps us recognise how the way information is presented can shape our decisions. We also see that other biases can interact with framing, further influencing our choices across many situations.

What is an example of how framing can influence decision-making?

When we hear that a medical procedure has a 90% survival rate, we feel more positive about it than if we hear there is a 10% chance of death, even though both statements mean the same thing. The way the outcome is framed changes our feelings and choices.

How does the framing effect differ from the anchoring bias?

Framing effect involves how information is presented as positive or negative, which then guides our decisions. Anchoring bias, on the other hand, happens when we rely too much on an initial number or fact (the “anchor”) when making choices. While both are cognitive biases, they shape our thoughts in different ways.

What role does framing play in medical decision-making?

Doctors and patients may choose different treatments based on whether risks or benefits are highlighted. For example, describing a treatment as having a “70% success rate” may encourage us to accept it, while saying there is a “30% failure rate” might make us hesitate, even though the facts are identical.

In what ways does the availability heuristic interact with framing when evaluating information?

If information is easy to remember or dramatic, we are more likely to notice and use it. When framing highlights certain details, the availability heuristic can make those details seem more important, pushing us towards specific decisions based on what comes most quickly to mind.

How can one minimise the impact of framing effects on their judgements?

We can pause to think about the actual data and ask ourselves if the information is being presented in a certain way to influence us. Looking at facts in both positive and negative frames helps us spot bias and make more careful choices.

What are the implications of the framing effect in psychological research and practice?

Framing can affect survey results, therapy decisions, and how findings are explained. If researchers or therapists are not careful, the way questions are asked or results are shared can shape responses. Being aware of this bias helps us collect better data and give more balanced guidance.